*

Το διήγημα «Το Κλήμα Λάζαρος» του Δ. Ε. Σολδάτου παρουσιάζεται θεατροποιημένο αυτό το Σάββατο 12.4.2025 –ανήμερα του Λαζάρου– από τον ηθοποιό Δημήτρη Βερύκιο (κιθάρα, μαντολίνο, τραγούδι: Αρετή Κοκκίνου) στον Ιερό Ναό των Αγίων Αναργύρων στου Ψυρρή. Ώρα έναρξης 19:15.

~.~

του ΔΗΜΗΤΡΗ Ε. ΣΟΛΔΑΤΟΥ

Μόνο εκεί που υπάρχουν τάφοι υπάρχει ανάσταση.

FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE

Δίπλ’ απ’ το πατρικό μου στο χωριό –εκεί που τώρα βρίσκεται το Silenus Bill’s Bar– υπήρχε παλιά ένα ελαιοτριβείο. Η ευωδιά του φρεσκοστυμμένου λαδιού φλόμωνε τα ρουθούνια μας. Απ’ τ’ άγρια χαράματα βοούσε το μελισσομάνι των λιτρουβιαραίων. Βογκούσαν τα τρακτέρ στην ανηφόρα, φορτωμένα σακιά τίγκα στον ελαιόκαρπο. Βουνό το λιοκόκκι. Άχνιζαν τα τσόλια στον φράχτη σαν γδαρμένα τομάρια. Κι εμείς –λιμασμένα παιδιά της γειτονιάς– κλωθογυρίζαμε εκεί γύρω, ώσπου κάποιος γνωστός να μας φωνάξει να ιδούμε τις μυλόπετρες που αλέθουν και να μας τρατάρει μια πρωμάδα: ψωμί πυρωμένο στην φωτιά, αλειμμένο με ζεστό φρέσκο λάδι. «Όταν μεγαλώσω», έλεγα, «θα γίνω λιτρουβιάρης! Θα πίνω ούζο 12 και θα καπνίζω άφιλτρα τσιγάρα Καρέλια».

Πριν προλάβω να μεγαλώσω, το λιτρουβιό έκλεισε. Το παραπάνω χωριό από το δικό μας ερήμωσε. Κι έτσι, το Δημοτικό Σχολείο μεταφέρθηκε στο εγκαταλελειμμένο ελαιοτριβείο, που το μισό διαμορφώθηκε σε διδακτικό χώρο και το άλλο μισό παρέμεινε κλειδωμένο, με σκουριασμένα καζάνια κι αραχνιασμένες μυλόπετρες. Καμιά φορά, κατά την διάρκεια του μαθήματος, ακούγαμε το «κριτς-κριτς» των ποντικών από δίπλα.

Κάποτε και το δικό μας χωριό άδειασε. Ο κόσμος πήγαινε στις μεγάλες πόλεις να βρει δουλειά. Το σχολείο έκλεισε. Μετακόμισε στον παρακάτω οικισμό. Και το παλαιό ελαιοτριβείο του Καμαρίλα νοικιάστηκε σε μια εξηντάχρονη Εγγλέζα μετρίου αναστήματος, με βαμμένο ξανθό μαλλί και αέρα φλεγματικής λαίδης. Κανείς δεν ήξερε τίποτα γι’ αυτήν. Μόνον πως την έλεγαν Τζόυ, που στην γλώσσα της θα πει Χαρά, μα οι χωριάτες το εκλάμβαναν ως Ζωή. Αμάξι δεν είχε. Έρχονταν και την έπαιρναν οι φίλοι της με τα δικά τους αυτοκίνητα και τα χαράματα την ξανάφερναν.

Ήταν γλεντζού!

Κυκλοφόρησαν πολλές φήμες για λόγου της, πως έτρεχε το χρήμα απ’ τα μπατζάκια της, πως είχε ιδιωτικό νησί στην πατρίδα της, αλλά βαρέθηκε την ζωή που έκανε και διάλεξε το μέρος μας για να περάσει τα τελευταία της χρόνια, αφήνοντας πίσω τις πολυτέλειες και τις ομίχλες της Αγγλίας και κάνοντας μια καινούργια αρχή κάτω απ’ τον λαμπρό ήλιο της Ελλάδας.

Με τον καιρό η Τζόυ άρχισε ν’ αλλάζει…

Οι φίλοι της αραίωσαν. Αν ήθελε κάπου να πάει, έπαιρνε ταξί ή πήγαινε με τα πόδια.

Έκανε παρέα με τις χωριάτισσες και μάθαινε την τοπική διάλεκτο που χρησιμοποιούσαν. Αποστήθιζε λευκαδίτικες εκφράσεις και τις αναπαρήγαγε με γεροντίστικη προφορά και παιδιάστικο σκέρτσο: «Επά’αινα ξώχειλα-ξώχειλα στην λιθιά, εξαχούρδησα, εσκουπ’λιάστ’κα κι εγένηκα μπ’κούνια!» Που πάει να πει: «Επήγαινα άκρη-άκρη στην λιθιά, ξαγλίστρησα, σωριάστηκα κι έγινα κομμάτια!»

Οι απλοϊκές γυναίκες ήταν πλέον οι αληθινές της φίλες.

Σηκώνονταν αχάραγα, ανάπιαναν προζύμι και ψήνανε ψωμί σε φούρνο με ξύλα. Της μάθαιναν λευκαδίτικα μαγειρέματα: κοκοτό με τιμάτσι, μακαρουνόπιτα και μπριάνι, τσιγαρίδια με προσφορίτες και σουπιές με μακαροτσίνι. Της έδειχναν πώς γίνεται το γλυκό κυδώνι: πελτές και κοφτό. Πώς φκιάνουνε καφέ μ’ αυγό, πώς πήζουνε στα κάρβουνα τ’ ασπράδι μες στο τσόφλι και μοιάζει με κορφούγκι. Πώς ψήνουν το κορφούγκι μες σε φύλλο από κουτσούνα και το τρώνε με ζάχαρη και κανέλλα. Αυτή μαθήτευε μ’ ενδιαφέρον περισσό. Κατόπιν έφκιανε μόνη της τα φαγιά και γύριζε στην γειτονιά και τα μοίραζε, για να ιδεί αν πέρασε τις εξετάσεις.

Μια μέρα έκαμε την μεγάλη ανακοίνωση: «Μην με ξαναπείτε Τζόυ! Πάει αυτή, πέθανε… Τώρα αναστήθηκα και με λένε Ζωή. Η Εγγλέζα γιοκ! Έγινα χωριάτισσα!» Κι έπιανε το ποτήρι με το ούζο και το κατέβαζε μονοκοπανιά, λέγοντας: «Γεια μας και καλά στερνά!»

Οι χωριάτισσες την λάτρεψαν, όπως λατρεύει ο καθένας κάποιον που θέλει να του μοιάσει, μα δεν της συγχώραγαν την ελευθεριότητά της σε όλα. Τις διαόλιζε η φήμη πως της άρεσαν πολύ οι άντρες.

Αυτές, που πέρασαν μια ζωή αγόγγυστα δίπλα σ’ ένα και μοναδικό αρσενικό κι ανταποκρίνονταν στα συζυγικά τους καθήκοντα δίχως προσωπική απόλαυση, δεν άντεχαν να ’ρχεται τώρα εκείνη –η ξένη– και να ξυπνάει μέσα τους την γυναίκα, που θάφτηκε δυο χιλιάδες χρόνια κάτω απ’ το θέλημα του αντρός και σκεπάστηκε κάθε της πόθος μ’ εκατό χιλιάδες μετάνοιες. Αν ήθελε να γίνει χωριάτισσα, έπρεπε να τις μοιάζει σε όλα. Ειδάλλως, είχαν ράμματα για την γούνα της…

Η Ζωή τα καταλάβαινε αυτά, αλλά ο δρόμος της έρχονταν από πολύ μακριά, για να χαθεί στις εσχατιές των ανθρώπων.

Κάποτε, μια φτωχή κοπέλα του χωριού παντρεύτηκε. «Η ξένη», όπως την έλεγαν οι ξινές, έβγαλε τον βαρύτιμο σταυρό της και τον κρέμασε στο λαιμό της νιόπαντρης. Όλοι θαύμασαν: «Τέτοιος σταυρός! Θα κάνει μια περιουσία…» Κι άρχισαν πάλι να οργιάζουν οι φήμες για τα πλούτη της, ενώ κάποιοι μεσόκοποι γαμπροί την νείρονταν πλέον ολοφάνερα κι έγλειφαν τα μουστάκια τους σαν γάτοι.

Τα χρόνια πέρασαν…

Η Ζωή κουράστηκε κι απ’ την ζωή της χωριάτισσας και κλείστηκε στον εαυτό της. Ζωγράφιζε πολύ ωραία! Κι έτσι, την έβλεπες στις εξοχές με το καβαλέτο ν’ αποτυπώνει στον καμβά λευκαδίτικα τοπία. Παλαιότερα, έφκιανε τα πορτραίτα των ανθρώπων του χωριού. Τώρα πουλιά και ζώα, δέντρα κι αγριολούλουδα, βάρκες κι ακροθαλάσσια.

*

*

Η παλιά αρθρίτιδα κάλπαζε…

Παραμορφώθηκαν τα δάχτυλα των χεριών και των ποδιών της. Με δυσκολία βάδιζε πλέον. Την έβρισκες στο καφενείο –όταν κατόρθωνε να φτάσει ως εκεί– να πίνει και να καπνίζει μανιωδώς, με τα γαλάζια μάτια της χαμένα στον ορίζοντα. Είχε αρχίσει να ξαναγίνεται Εγγλέζα.

Μια μέρα, την είδα στην αυλή της να κρατάει ένα τσαπί.

«Τι κάνεις εκεί, Ζωή;» την ρώτησα.

«Φυτεύω ένα κλήμα!» μου απάντησε, με μια λάμψη στα ξεθωριασμένα της μάτια, ακριβώς όταν πρόφερε την λέξη «φυτεύω».

Το κλήμα, όμως, δεν έπιασε στο χώμα εκείνο κι έμεινε η βέργα ξερή κι αρούγκανη. Η Ζωή ήταν απαρηγόρητη! Αφού δοκίμασε με όλους τους τρόπους να κρατήσει το κλήμα ζωντανό, κατάλαβε πως το φυτό είχε πλέον πεθάνει. Προσφερθήκαμε να της δώσουμε μιαν άλλη βέργα να φυτέψει – δεν καταδέχτηκε…

Ένα πρωί, μόλις ξύπνησα κι άνοιξα το παράθυρο, είδα την Ζωή να ποτίζει την ξερή βέργα και να της μιλάει: «Καλημέρα, κληματάκι!» Αυτό το βιολί συνεχίστηκε ολόκληρη την εβδομάδα: «Καλημέρα, κληματάκι! Καληνύχτα, κληματάκι! Σ’ αγαπώ πολύ, κληματάκι!»

Δεν ήξερα τι να κάνω, να γελάσω ή να κλάψω με την ανοησία ή την ευαισθησία αυτής της γυναίκας;

Οι γειτόνοι χασκογέλαγαν πίσω απ’ την πλάτη της και την κορόιδευαν μιμούμενοι την φωνή της: «Καλημέρα, κληματάκι! Καληνύχτα, κληματάκι!» Μα σε λίγο καιρό ανησύχησαν στ’ αλήθεια και ψιθύριζαν πως άρχισε σιγά-σιγά να το χάνει…

Δεν πήγαινε άλλο! Αποφάσισα να της μιλήσω.

Εκείνη με άκουσε υπομονετικά. Ύστερα πήρε στα χέρια της ένα χοντρό μαύρο βιβλίο κι έψαξε μια σελίδα, την βρήκε και ξεκίνησε να διαβάζει:

«Εἶπεν αὐτῇ ὁ ᾿Ιησοῦς· ἐγώ εἰμι ἡ ἀνάστασις καὶ ἡ ζωή. Ὁ πιστεύων εἰς ἐμέ, κἂν ἀποθάνῃ, ζήσεται· καὶ πᾶς ὁ ζῶν καὶ πιστεύων εἰς ἐμὲ οὐ μὴ ἀποθάνῃ εἰς τὸν αἰῶνα. Πιστεύεις τοῦτο;»

Νόμισα πως η ερώτηση απευθύνονταν σ’ εμένα κι όχι πως περιλαμβάνονταν στο χωρίο, αλλά εκείνη έσπευσε να διευκρινίσει:

«Κατά Ιωάννην Ευαγγέλιο! Είναι το σημείο που μιλάει για την ανάσταση του Λαζάρου».

Κάτι πήγα να πω, αλλά μου έκαμε νόημα να σωπάσω και συνέχισε την ανάγνωση:

«Καὶ ταῦτα εἰπὼν φωνῇ μεγάλῃ ἐκραύγασε· Λάζαρε, δεῦρο ἔξω. Καὶ ἐξῆλθεν ὁ τεθνηκὼς δεδεμένος τοὺς πόδας καὶ τὰς χεῖρας…»

Έκλεισε το βιβλίο και, σκύβοντας λιγάκι προς το μέρος μου, είπε σε τόνο εμπιστευτικό:

«Ονόμασα το νεκρό μου κλήμα Λάζαρο. Τώρα, του λέω κάθε μέρα ν’ αναστηθεί. Κι επειδή το θέλω πολύ και πιστεύω με όλη μου την ψυχή πως αυτό θα συμβεί, περιμένω να ζωντανέψει!»

Την κοίταζα άφωνος, ανέκφραστος σαν Βούδας, «κι έγινε το γεφύρι της σιωπής η βαθιά μας ομιλία…» Δεν ήταν πλέον η Ζωή, στα μάτια μου φάνταζε γαλανομάτα δυτική Παναγία. Κι αποφάσισα ν’ αλλαξοπιστήσω:

«Κι εγώ το πιστεύω!» της είπα. «Κι αν θέλεις, μπορώ να έρχομαι κάθε μέρα να του διαβάζω Όμηρο στο πρωτότυπο. Ξέρεις, τα κλήματα υπάρχουν χιλιάδες χρόνια σ’ αυτόν τον τόπο. Δεν μπορεί, όλο και κάτι θα θυμάται το DNA του από εκείνη την υπέροχη γλώσσα!»

Συμφωνήσαμε. Κι απ’ το άλλο πρωί, ο ζουρλομανδύας που ετοίμαζαν οι χωριάτες άρχισε να ράβεται και για τους δυο μας.

Με τις πρώτες αχτίδες του ήλιου: «Καλημέρα, κληματάκι! Σ’ αγαπάμε πολύ, κληματάκι!» Κι ύστερα ποτίζαμε τον Λάζαρο δροσερό νεράκι, κι άνοιγα την Ιλιάδα:

«Μῆνιν ἄειδε, θεὰ, Πηληϊάδεω Ἀχιλῆος οὐλομένην, ἣ μυρί᾿ Ἀχαιοῖς ἄλγε᾿ ἔθηκε, πολλὰς δ᾿ ἰφθίμους ψυχὰς Ἄιδι προΐαψεν ἡρώων…»

Την επομένη τα ίδια: «Καλημέρα, κληματάκι! Σ’ αγαπάμε πολύ, κληματάκι!» Κατόπιν πάλι νεράκι. Και σειρά είχε αυτήν την φορά η Οδύσσεια:

«῎Ανδρα μοι ἔννεπε, Μοῦσα, πολύτροπον, ὃς μάλα πολλὰ πλάγχθη, ἐπεὶ Τροίης ἱερὸν πτολίεθρον ἔπερσε· πολλῶν δ’ ἀνθρώπων ἴδεν ἄστεα καὶ νόον ἔγνω…»

Και το «Καλημέρα, κληματάκι! Σ’ αγαπάμε πολύ, κληματάκι!» συνεχίζονταν μέχρι την Σαπφώ:

«Δέδυκε μὲν ἀ σελάννα καὶ Πληΐαδες·/ μέσαι δὲ νύκτες,/ παρὰ δ᾿ ἔρχετ᾿ ὤρα,/ ἔγω δὲ μόνα κατεύδω»: «Αχ, το φεγγάρι κρύφτηκε κι η Πούλια! Πια ζυγώνει/ το μεσονύχτι. Η ώρα περνά κι εγώ κοιμάμαι μόνη», μετέφραζα ομοιοκατάληκτα.

Η Ζωή με χάζευε να δίνω την καθημερινή παράσταση. Κι εγώ ευχαριστιόμουν που επιτέλους μπορούσα κάπου ν’ απαγγέλω τα χωρία που αγαπούσα, έστω και σ’ ένα κλήμα που περίμενα… ν’ αναστηθεί!

«Ἔρως ἀνίκατε μάχαν,/ Ἔρως, ὃς ἐν κτήνεσι πίπτεις,/ ὃς ἐν μαλακαῖς παρειαῖς νεάνιδος ἐννυχεύεις…»: «Έρωτα ακατανίκητε, τον κόσμο κυριεύεις./ Σε πέλαγα, στεριές πετάς και στους πιο κρύφιους τόπους,/ στων κοριτσιών τα τρυφερά μάγουλα νυχτερεύεις/ κι ίδια τρελαίνεις τους θεούς και τους θνητούς ανθρώπους», έλεγε ο Σοφοκλής. Και συνέχιζε η Αντιγόνη: «Οὒτοι συνέχθειν, ἀλλά συμφιλεῖν ἔφυν»: «Δεν γεννήθηκα για να μισώ αλλά για να αγαπώ».

Επιστράτευσα και το δημοτικό τραγούδι:

«Αμπέλι μου πλατύφυλλο και κοντοκλαδεμένο,/ για δεν ανθείς, για δεν καρπείς, σταφύλια για δεν κάνεις;/ Με χρέωσες, παλιάμπελο, και θέλ’α σε πουλήσω./ Μην με πουλάς, αφέντη μου, κι εγώ σε ξεχρεώνω!/ Για βάλε νιους και σκάψε με, γέρους και κλάδεψέ με,/ και κοριτσάκια ανύπαντρα να με κορφολογούνε».

Η Ζωή χτύπαγε παλαμάκια ενθουσιασμένη, λες και χόρευαν οι λέξεις Πυρρίχιο, Απόκινο κι Επιλήνιο μες στα χείλη μου. Κι όσο μεγάλωνε ο χορός των λέξεων και σχηματίζονταν φράσεις και χωρία ολόκληρα, τ’ αρχαία βήματα έσμιγαν με τα τωρινά –Συρτό, Αντικριστό και Τσάμικο– και πάλλονταν το στήθος μας από συγκίνηση, λες κι ένας αόρατος απινιδωτής διέχεε ηλεκτρικό ρεύμα στο κορμί μας, κατόπιν θανατηφόρας καρδιακής αρρυθμίας. Ένα τέτοιο ηλεκτροσόκ χρειάζονταν και το πεθαμένο κλήμα! Τα σώματά μας –σαν συγκοινωνούντα δοχεία– συντονίζονταν στον παλμό της επιθυμίας να επιτευχθεί το αδύνατον, ο παλμός διαχέονταν απ’ τις φλέβες στο δέρμα, που σαν τεντωμένο τομάρι τυμπάνου –σε όργιο διονυσιακό ή σε πανηγύρι δεκαπενταύγουστου– μετέδιδε τον κραδασμό από μας προς τα έξω, από τα έμψυχα προς τα άψυχα, βυθίζονταν στο χώμα –όπως κεραυνός απ’ τ’ αλεξικέραυνο– έβρισκε τις μαυρισμένες ρίζες του κλήματος και τις πύρωνε σαν παγωμένες αρτηρίες, προσδοκώντας ανάσταση νεκρών – μια Δευτέρα Παρουσία εδώ και τώρα!

Πέρασε μήνας, κι ο Λάζαρος έμενε βέργα ξερή κι αρούγκανη. Εγώ είχα αρχίσει να κουράζομαι. Μια μέρα πήγαινα, μια δεν πήγαινα, ώσπου κάποτε σταμάτησα.

Η Ζωή δεν μου κράτησε κακία για την ολιγοπιστία μου και συνέχιζε μόνη της:

«Καλημέρα, κληματάκι! Σ’ αγαπώ πολύ, κληματάκι!»

Την άκουγα ανοίγοντας το παράθυρο και μάτωνε η ψυχή μου. Τι σταυρό πρέπει να κουβαλάει ένας άνθρωπος, ώστε να φύγει απ’ τον τόπο του, να πάει σ’ ένα σχεδόν έρημο χωριό, να μείνει σ’ ένα εγκαταλελειμμένο λιοτρίβι και να προσπαθεί ν’ αναστήσει ματαίως ένα κλήμα νεκρό;

Κάποτε πέρασε απ’ τον νου μου μια ιδέα τρελή: να κλέψω ένα βράδυ την ξερή βέργα και να βάλω στην θέση της μιαν άλλη, που θα είχε ξεπετάξει μερικά μπουμπούκια. Όμως αυτό θα έμοιαζε σαν την κλοπή του σώματος του Ιησού απ’ τους μαθητές του, δηλαδή με μια ψεύτικη ανάσταση. Αν συνέβαινε κάτι τέτοιο, ολόκληρος ο Χριστιανισμός θα στηρίζονταν σε μιαν απάτη. Στην περίπτωσή μου, όλη η πίστη της Ζωής θα βασίζονταν στο θαύμα που τέλεσε η απιστία μου.

Ποιος ξέρει, ίσως η μοναχική αυτή γυναίκα, τώρα στα τελευταία της, ν’ απέθετε την στερνή ελπίδα της στον Θεό, στην μεταθανάτια ζωή, και το κλήμα Λάζαρος να ήταν η απόδειξη πως δεν τελειώνουν όλα εδώ, πως «πᾶς ὁ ζῶν καὶ πιστεύων κἂν ἀποθάνῃ, ζήσεται».

Ένα σαββατιάτικο δειλινό, την ώρα που η καμπάνα σήμαινε για τον εσπερινό, ακούστηκε ανακατωμένη με τους χαρμόσυνους ήχους η φωνή της Ζωής:

«Αναστήθηκε… Αναστήθηκε! Το κλήμα Λάζαρος είναι ζωντανό!»

Πεταχτήκαμε όλοι έξω και είδαμε ιδίοις όμμασι το παράδοξο: ένα ίχνος μπουμπουκιού πρόβαλε στην βέργα, σχεδόν αόρατο, αλλά ο καθείς μπορούσε να ξεχωρίσει πως εδώ υπήρχε ζωή! Κάποιοι έκαμαν τον σταυρό τους, όχι γιατί σήμαινε η καμπάνα, αλλά επειδή χτυπούσε την πόρτα της καρδιάς τους το θαύμα.

Σε λίγο διάστημα το μπουμπούκι –«ματάκι» το λέμε στο χωριό– έβγαλε φύλλα, κάτι βελούδινα πράσινα φυλλαράκια, σαν φτερά πεταλούδας βουτηγμένα στην λουλουδόσκονη. Καινούργια ματάκια πρόβαλαν κατόπιν και μετά κι άλλα, ώσπου το κλήμα Λάζαρος αναστήθηκε για τα καλά και τυλίχτηκε πάνω στο καλάμι κι ανέβαινε και θέριευε ολοένα…

Τώρα, όσοι περνούσαν από κει έλεγαν τρυφερά:

«Καλημέρα, Ζωή! Καλημέρα, κληματάκι!» αλλά δίχως ίχνος ειρωνείας στην φωνή τους αυτήν την φορά. Κι όταν μαραίνονταν μια γαρυφαλλιά ή μια τριανταφυλλιά φαγώνονταν απ’ την μελίγκρα ή μια λεμονιά καιγόντανε απ’ το χαλάζι, θυμόνταν το κλήμα Λάζαρο και μιλούσαν κι εκείνοι στο ανήμπορο φυτό ή δέντρο, ελπίζοντας σ’ ένα θαύμα.

Δεν πέρασε πολύς καιρός, και η Ζωή έφυγε απ’ το χωριό. Αγόρασε ένα χωράφι απέναντι απ’ το νεκροταφείο κι έχτισε εκεί ένα σπιτάκι. Ήθελε να ’ναι κοντύτερα στην πόλη, μιας και τα προβλήματα υγείας της χειροτέρεψαν. Όλο και πιο σπάνια την συναπαντούσαμε.

Κάποια φορά πήγα να την δω. Ήταν φανερά καταβεβλημένη. Με ρώτησε για το κλήμα Λάζαρο. Της είπα πως θα βγάλει σταφύλια σε λίγο καιρό και θα της φέρω, για να μοσκοβολήσει το στόμα της απ’ την γεύση της πίστης. Χαμογέλασε πικρά. Το βλέμμα της είχε ξεθωριάσει τόσο! Θύμιζε πλέον την ομίχλη της πατρίδας της. Κοιτούσε τα καντηλάκια του νεκροταφείου, που τρεμόπαιζαν στο μισοσκόταδο, και σιωπούσε…

Έσβησε ξαφνικά! Δεν πρόφτασε να γευτεί τα σταφύλια.

Αν κι είχε αγοράσει τάφο στο χωριό, την μετέφεραν να θαφτεί στην Αγγλία. Το σπίτι της πουλήθηκε εν μια νυκτί. Εκεί που κατοίκησε η μοναξιά της, ήρθαν άλλοι: με παιδιά, με σκυλιά, μ’ αυτοκίνητα. Τα ίχνη της χάθηκαν, οι χωριάτισσες που την θυμόνταν ξέχασαν, γέρασαν, πέθαναν.

Το κλήμα Λάζαρος, όμως, υπάρχει ακόμα – μέχρι σήμερα!

«Πᾶς ὁ ζῶν καὶ πιστεύων εἰς ἐμὲ οὐ μὴ ἀποθάνῃ εἰς τὸν αἰῶνα. Πιστεύεις τοῦτο;»

ΔΗΜΗΤΡΗΣ Ε. ΣΟΛΔΑΤΟΣ,

Λευκαδίτικα διηγήματα,

Fagotto Books, 2018

(3η εμπλουτισμένη έκδοση)

///

«Το Κλήμα Λάζαρος» μεταφράστηκε στην αγγλική (μητρική γλώσσα της ηρωίδας του διηγήματος) για να τιμήσει την Ζωή με τον ίδιο τρόπο που τίμησε κι εκείνη την γλώσσα μας, μαθαίνοντας ελληνικά και μάλιστα την ντοπιολαλιά της Λευκάδας, καθώς και για να διαβαστεί από τους Άγγλους συγγενείς και φίλους της, εδώ και στο εξωτερικό, που θα ήθελαν να γνωρίζουν αυτήν την ιστορία.

“Vine Lazarus” was translated into English (the mother tongue of its heroine) in order to honor Zoe the way she herself had honored our language by learning not just Greek but the Lefkada dialect as well. Also, in order to be read by her English friends and relatives, here or abroad, who might be interested in this story.

~.~

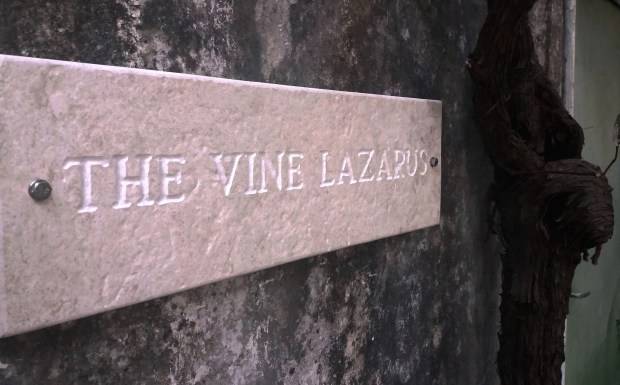

The Vine Lazarous

by DIMITRIS E. SOLDATOS

Only where there are graves there are resurrections.

FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE

Νext to my family home in the village –where “Silenus Bill’s Bar” now stands– there was once an olive press. The odor of the freshly pressed oil filled up our nostrils. At the crack of dawn, the oil mill workers, ready for the day’s pressing, buzzed like bees. Tractors carrying sacks filled to the brim with olives, clambered up the hill road. The olive kernels formed a huge heap. The oil filters stretched on the thorny wire fence resembled steaming skins of slaughtered animals. We, the neighborhood kids, were roaming about until someone would call us to come watch the grinding mill stones and would then offer us a “promada”: roasted bread, with a spread of fresh hot oil. “When I grow up”, I used to tell myself, “I will become the proprietor of an olive press. I will be drinking Ouzo 12 and smoking non filtered Karelia cigarettes”.

Before I came of age the olive press was shut down. The village above our own was deserted. So the public school was transferred to the abandoned olive press property, half of it transformed into a teaching place, half of it remaining locked, with its boilers rusting away among the cobwebbed mill stones. Sometimes, during lessons, we could hear the squeaks of mice from next door.

Gradually, our own village also lost its inhabitants. People were migrating to the big cities in search of work. The school closed down. They moved it to a neighboring village. As for the olive press building, a sixty year old English lady came to rent it. She was of medium stature, with short blond hair and a phlegmatic air. No one knew a thing about her. Only that she was called Joy, a name which the peasants took as meaning “life” in Greek. She didn’t have a car. Her friends usually picked her up with their own cars, bringing her back in the wee hours of the morning.

She was a merrymaker.

There was a lot of gossip about her. People said that she was filthy rich, yet one day got bored of the way she was living and chose our place to spend the last years of her life, leaving the luxuriousness and mists of England behind, to make a brand new start under the Greek bright sun.

As time went by, Joy begun to slowly change…

Her friends stopped showing up. If she decided to go somewhere, she either took a taxi or went on foot.

She befriended the peasant women and learned the local dialect by writing down on a notebook the words and phrases they used. She managed to memorize various verbal expressions of Lefkada, which she reproduced with a funny pronunciation and childish charm.

The simple-minded village women were now her real friends.

They woke up at dawn, prepared fresh sourdough and baked bread in the wooden ovens. They taught Joy how to cook the island’s special recipes and she absorbed all the information needed. She then went around the neighborhood with the foods she had prepared, offering everyone samples in order to find out if she had passed the cooking test.

One day she made a big announcement: “Don’t call me Joy again! That one is dead… I have been resurrected and my name is Zoe (“life” in Greek). The Englishwoman is no more! I am now a villager, just like you”. And she grabbed her glass of ouzo, drank it all in one gulp, and said: “Cheers! Here’s to a good old age!”

The peasant women adored her, like we adore anyone who wants to become like us. On the other hand, they could not forgive her free spirit. They were scandalized by the rumor that Zoe unashamedly enjoyed male company.

These women had spent all their adult lives by the side of just one man and performed their marital duties without deriving any pleasure for themselves. Therefore, they could not stand the thought of this foreigner reminding them of the woman inside them who, buried under man’s thumb for thousands of years, was constantly repenting for her desires. If Zoe wanted to be a true peasant, she had to look and act exactly like them or else they would keep on bad-mouthing her…

Zoe was well aware of this, but she had come a long way and was not planning to be lost in the badlands of human pettiness.

One day, a poor village girl got married. The “foreigner”, as the ill-natured ones called Zoe, took off her valuable cross and put it around the young bride’s neck. Everyone was dumbfounded: “What a cross! Surely it must cost a fortune…” Rumors about her wealth started raging again, making middle-aged yet still single villagers lick their moustaches like cats at the prospect of marrying her.

Years went by…

Zoe got tired of living like a simple peasant woman and withdrew into herself. She was always a skillful painter! One would often spot her in the countryside with an easel, depicting on her canvas various landscapes of Lefkada. In the past she used to make portraits of peasants. Now she only did birds and animals, trees and wild flowers, boats and seashores.

Meanwhile, her old arthritis was galloping…

The fingers of her hands and feet slowly became distorted. She was barely able to walk anymore. You would see her in the coffee shop, whenever she had managed to get there, drinking and smoking like a maniac, her blue eyes lost in the horizon. She was turning into an Englishwoman again.

One day, I saw her standing in her yard, holding a pickaxe.

“What are you doing there, Zoe?” I asked her.

“I am planting a vine”, she replied, and a glow lit her faint eyes when she pronounced the word “planting”.

But the vine was unable to grow in that soil and the shoot remained dry. Zoe was inconsolable! After trying every method possible to keep the vine alive, she finally came to realize that the plant was dead. We offered her a new branch to plant but she didn’t accept it…

One morning, when I woke up and looked through my window, I saw Zoe watering the dried shoot and speaking to it. “Good morning, little vine!”, she was saying. This strange practice continued all week, day and night. “Good morning, little vine!” “Good night, little vine!” “I love you dearly, little vine!”

I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry at the stupidity or the sensitivity of that woman.

The other neighbors were certainly laughing behind her back, they joked and mimicked her voice: “Good morning, little vine! Good night, little vine!” But as time went by they started really worrying and whispering to each other that the Englishwoman had lost her mind…

I had had enough! I decided to go talk to her.

She listened to me patiently. Then she took out a thick black book, searched for a certain page, found it and started to read:

“Jesus said to her, I am the resurrection and the life. The one who lives in Me and believes in Me will live even though they die. And whoever lives by believing in Me will never die. Do you believe this?”

For a moment I thought the question was directed at me and not included in the passage, but she hurried to explain:

“The Gospel of John! It’s where John speaks about the resurrection of Lazarus”.

I tried to say something but she silenced me with a nod and went on reading: “Then Jesus shouted· ‘Lazarus, come out!’ And the dead man came out, his hands and feet bound in grave clothes…”

She then closed the Holy Bible and leaning towards me said in a confidential tone:

“I have named my dead vine Lazarus. Now every day I ask it to resurrect. And because I want this to happen and deeply believe that it will happen, I am waiting for it to come back to life!”

I stared at her speechless, expressionless like Budda, “and the bridge of silence became our significant conversation…” For me she was no longer Zoe, she had been transformed into a blue eyed Virgin Mary of the Catholic Church. And I decided to be proselytized:

“I also believe that!” I told her. “And if you want me to, I can come every day and read Homer to it from the original text. Vines existed in this place for thousands of years. I am sure the vine’s DNA will be able to recall something of that wonderful language!”

We agreed on that. And from next morning on, the straight jacket that the peasants were preparing for her, was being sewed for me as well.

With the first rays of the sun every day: “Good morning, little vine! We love you, little vine!” Then Lazarus was offered cool water, and after that, I opened the book of Iliad and read:

“The wrath sing, goddess, of Peleus’ son Achilles, the accursed wrath which brought countless sorrows upon the Achaeans, and sent down to Hades many valiant souls of warriors…”

Next day, the same ritual:

“Good morning, little vine! We love you dearly, little vine!” Then water again. Then it was Odyssey’s turn:

“Sing in me, Muse, and through me tell the story of that man skilled in all ways of contending, the wanderer, hurried for years on end, after he plundered the stronghold on the proud height of Troy. He saw the town lands and learned the minds of many distant men…”

And “Good morning little vine! We love you dearly, little vine!” was then followed by Sappho’s lines, “The moon is set and the Pleiades too/It’s the middle of the night/Time passes and I sleep alone”.

While I was giving my everyday show, Zoe was looking at me excitedly. As for myself, I was happy to finally be able to recite the ancient passages I loved, even if to a vine I was expecting… to come to life!

“Eros, unbeatable in battle/ Eros, you who destroy possessions/you who stand sentry by/ young girls’ gentle cheeks/ and roam overseas to / pastoral courts: both Gods and mortals are driven mad by you”, Sophocles was saying. And Antigone continued: “I was not born to hate but to love”.

I even resorted to Greek folk songs:

“My broad leafed and short cut vine/ why don’t you blossom and thrive/ why don’t you give us grapes?/ You got me into dept, bloody vine, I’ll put you up for sale./ Don’t sell me, master, I will thrive/ Have young men spade me, old men crop me/ and unmarried girls trim my sprouts”.

Zoe, delighted, was clapping her hands, as if the words were dancing Pyrrichios, Apokinos and Epilinios in between my lips. While the word dance progressed, forming sentences and whole passages, the ancient dance steps blended with more contemporary ones – Syrtos, Αntikristos, Τsamikos – and our chests throbbed with emotion, as if an invisible defibrillator was applying electric current through our bodies after a lethal bout of heart arrhythmia. It was the kind of electric shock the dead vine needed too. Our bodies –like communicating vessels– were synchronizing to the pulse of our desire to achieve the unachievable, the pulse was spreading out from the veins to the skin, which, like a stretched drumhead –in a Dionysian orgy or a 15th of August fest– transmitted our vibration outwards, from the animate to the inanimate, then dipped into the ground –like thunder from a lightning rod– found the blackened roots of the vine, those frozen arteries, and thawed them, awaiting the resurrection of the dead – a Second Coming here and now!

A month went by. Lazarus still remained a dried root. I was getting weary and started losing my religion. One day I was going to her place, the next day I was not, until I stopped visiting altogether.

Zoe didn’t hold a grudge against me for my unfaithfulness and continued the ritual by herself:

“Good morning, little vine! I love you dearly, little vine!”

I heard her voice every time I opened my window and my heart bled. Who knows what makes a person abandon their homeland, take refuge in a half-deserted village, live in an old oil mill, and then try in vain to resurrect a dead root?

One day, I came up with a crazy idea: I could sneak into her yard at night, uproot the dry shoot and put another, budding one, in its place. But this would be like the disciples secretly stealing the dead body of Christ, in order to fake his resurrection. If something like that had ever happened, then the whole Christian faith would have been based upon a fraud. In our case, all Zoe’s faith would then be based upon the miracle my infidelity had produced.

Who knows? Perhaps this lonely lady, now nearing the end of her days, wanted to place her ultimate hope in the hands of God, in the afterlife, and the vine Lazarus would be the proof that everything does not end here, that “everyone who lives and believes will live even if they die”.

Yet, one Saturday evening, when the church bells started tolling for the vespers mass, we heard Zoe’s happy voice mingled with the bells’ joyful sound:

“Resurrected… Resurrected! The vine Lazarus is alive!”

We all rushed out of our houses and witnessed the paradox: a vestige of bud had appeared on the shoot, invisible almost, yet everyone could see that a life was being born! A few people made the sign of the cross, not because the church bells were tolling, but because the miracle was knocking on the door of their hearts.

Soon after, the bud –we call it “mataki”/little eye, in the village– sprouted leaves, velvety small green leaves, like butterfly wings doused in pollen. New buds begun appearing, and then more, until the vine Lazarus was fully resurrected and was climbing up the reed…

*

*

From that day on, anyone passing by Zoe’s house, tenderly called out:

“Good morning, Zoe! Good morning, little vine!” without the slightest hint of irony anymore. And whenever a carnation or a rose bush was eaten up by greenflies or a lemon tree was burnt by hail, the villagers would immediately remember the vine Lazarus and start speaking lovingly to the sick plant or tree, hoping for a miracle.

Not long afterwards, Zoe left the village. She bought a plot of land opposite the cemetery, and there she built a little house. She wanted to be closer to town, since her health was deteriorating. We rarely saw or crossed paths with her anymore.

I went to visit her once. She was pale and haggard. She asked me about the vine Lazarus. I told her that it was about to bear grapes, and promised to bring her some, in order for her to taste the aroma of her faith. She smiled bitterly. Her eyes had grown so dim! They brought to mind her country’s mists. She was looking towards the small candles of the cemetery flickering in the dark, and kept silent…

Her own candle was suddenly put off! She died before getting to taste the grapes.

Although she had bought a grave in the village cemetery, her body was transported to England to be buried there. Her house was sold overnight. Other people came to inhabit the place that had housed her loneliness, people with children, dogs, cars. Her trails were lost, the peasant women that still remembered her, got old, died.

The vine Lazarus, however, exists still, even to this day!

“Whoever lives by believing in Me, will never die. Do you believe this?”

Translated by T.K.

DIMITRIS E. SOLDATOS,

Short stories from Lefkada,

Fagotto Books, 2018

3rd revised edition (in Greek)

*

*

*

*

*